Wisconsin Supreme Court Justice Brian Hagedorn, who is supposedly a conservative, was wrong to join the court’s liberal majority in refusing to immediately take up President Donald Trump’s voter fraud lawsuit.

Hagedorn has increasingly disappointed conservatives with his string of decisions joining the liberals on the court. He has some defenders in Republican circles who argue he’s just upholding the rule of law (which was his argument), despite the fact that conservative justices have consistently had different interpretations of the law.

Wisconsin voters have a right to know whether Trump’s claims have merit – or not – before the electoral college votes on Dec. 14. Hagedorn and the court’s liberals are stripping Wisconsin voters of that right.

The Four Reasons Why Hagedorn Was Wrong:

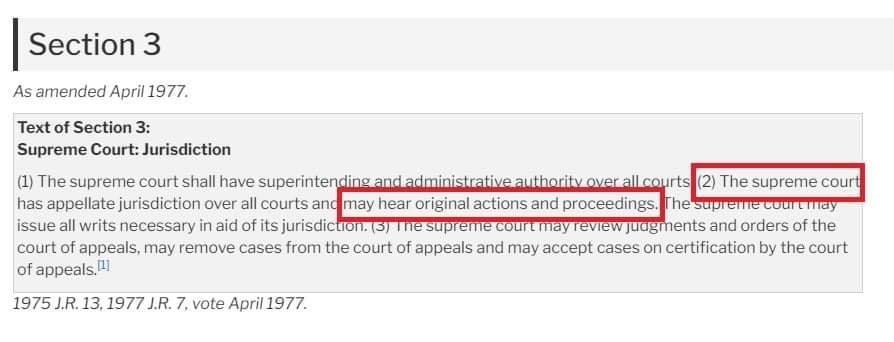

1. The Wisconsin Constitution Allows the State Supreme Court to Hear the Case Immediately

Hagedorn argues that state statutes mandate that the voter fraud lawsuit start out in Circuit Court. However, the conservative justices pointed out that the Wisconsin Constitution gives the state Supreme Court authority to hear what is called an “original action” – essentially hearing the case immediately, bypassing circuit and appellate courts. Indeed, they say, the Constitution trumps the state statutes that Hagedorn hinges his opinion on.

Read that section of the state Constitution here.

Hagedorn pretty much ignores this constitutional authority, although, in one line, he appears to acknowledge the court may have it.

Hagedorn wrote, “Even if this court has constitutional authority to hear the case straightaway, notwithstanding the statutory text, the briefing reveals important factual disputes that are best managed by a circuit court…”

But Conservative Justice Pat Roggensack, in a dissent joined by Annette Ziegler, wrote that the Wisconsin Constitution gives the Supreme Court authority to immediately take up the case. Furthermore, she offered a compromise to Hagedorn’s factual dispute concern – the circuit courts would do the fact-finding but the Supreme Court would decide.

“I conclude that we have subject matter jurisdiction that enables us to grant the petition for original action pending before us,” she wrote. “Our jurisdiction arises from the Wisconsin Constitution and cannot be impeded by statute.” She also wrote that time was of an essence.

Roggensack noted no statute “can circumscribe the constitutional jurisdiction of the Wisconsin Supreme Court to hear this(or any)case as an original action. The Wisconsin Constitution IS the law—and it reigns supreme.”

By ignoring the Constitutional question, Hagedorn is adopting too narrow a view of the “rule of law.”

There is precedent for this. It’s not like no one has ever had an original action accepted by the court before.

As a previous court case noted, “Under Wis. Stat. § 809.70, a person may request that the Wisconsin Supreme Court take jurisdiction of an original action. Whether the court does take jurisdiction is entirely within the court’s discretion.”

The Wisconsin Bar Association states that “petitions for bypass may be granted when the supreme court determines that there is a need to hasten the appellate process” and state statutes outline the criteria needed for such a petition.

The Bar Association notes that an appellate court petitioned the Supreme Court to take a lawsuit involving Scott Walker’s Act 10 reforms outright, saying it belonged before the highest court instead “because of its sweeping statewide effect on public employers, public employees, and taxpayers and because of the need to clarify and develop law relating to associational rights and the home-rule authority of municipalities.”

The election is just as sweeping. According to the Bar, “a recent example of an action for original jurisdiction in the supreme court occurred in State ex rel. Ismael R. Ozanne v. Fitzgerald. In this case, the supreme court exercised original jurisdiction in order to determine whether the Wisconsin Legislature acted unconstitutionally when it enacted 2011 Wisconsin Act 10.”

2. There’s No Time to Wait

Thus, we’ve established that the Wisconsin Constitution gives the state Supreme Court the right to take the case. There’s a pressing need to do so, and that’s because time is running out to give voters remedy if warranted.

The electoral college meets on December 14. Yet, Hagedorn would throw complex issues – involving absentee ballots and Democracy in the Park and so on – into a lengthy circuit court and then appellate court process.

That might work for some cases, but it’s easy to see why it wouldn’t work in this case.

Roggensack made this point, when she emphasized that “by denying this petition, and requiring both the factual questions and legal questions be resolved first by a circuit court, four justices of this court are ignoring that there are significant time constraints that may preclude our deciding significant legal issues that cry out for resolution by the Wisconsin Supreme Court.”

3. The Questions Have Statewide & Potentially National Impact

This case is not like many others. It contains questions that would surely have statewide impact, and potentially even national impact, which is why the state Supreme Court is the proper forum.

Justice Rebecca Bradley noted that such matters are exactly when the court should take a case immediately (original jurisdiction). “The court reserves this exercise of its jurisdiction for those original actions of statewide significance,” like an election, she wrote.

The Wisconsin Bar Association notes, “The concept of original jurisdiction allows cases involving matters of great public importance to be commenced in the supreme court in the first instance.”

What could be a matter of greater public importance than this?

The Trump campaign, in its lawsuit, outlined the “reasons why this court should take jurisdiction.”

The campaign said the matters “satisfy the criteria for this Court’s exercise of its original jurisdiction under Article VII, Section 3 of the Wisconsin Constitution.”

“This is an ‘exceptional case in which a judgment by the court [would] significantly affect the community at large,” the lawsuit says, citing a 2001 case Wisconsin Professional Police Association vs. Lightbourn. That case involved arguments relating to the state retirement system.

“This case involves the election for the electors of the Office of President and Vice President of the United States and the outcome of the recount and this matter will not only decide which candidates obtain Wisconsin’s 10 Electoral College Electors, but may very well decide the outcome of the election nationwide,” the Trump campaign wrote.

“Prompt resolution of this legal dispute is of the essence to the public interest because, absent this Court’s action, in-person absentee ballots without a corresponding written application, incomplete and altered-certification absentee ballots, all indefinitely confirmed absentee ballots, and ‘Democracy in the Park’ absentee ballots, will be included in the results of the Election despite clear and unambiguous law to the contrary.”

4. Delaying the Case Puts the Decisionmaking Authority in the Hands of the Unelected Wisconsin Election Commission

Should the state’s highest court weigh in on the manner in which election clerks acted in accordance (or lack thereof) to state law? Or do you prefer that the unelected Wisconsin Election Commission, currently dominated by two outspoken large Joe Biden donors and trial attorneys, has the final say before the electoral college votes?

We think the elected court is the better arbiter. Yet Hagedorn’s decision means it’s the WEC that will be the prevailing decider of these questions before the December 14 deadline.

Conservative justice Rebecca Bradley made this point in her dissent, which Roggensack and Ziegler also joined. She wrote,

The Wisconsin Supreme Court forsakes its duty to the people of Wisconsin in declining to decide whether election officials complied with Wisconsin’s election laws in administering the November 3, 2020 election. Instead, a majority of this court passively permits the Wisconsin Elections Commission (WEC) to decree its own election rules, thereby overriding the will of the people as expressed in the election laws enacted by the people’s elected representatives. Allowing six unelected commissioners to make the law governing elections, without the consent of the governed, deals a death blow to democracy.

The WEC has already made a host of controversial decisions, such as booting the Green Party off the ballot.

Table of Contents

![WATCH: Elon Musk Town Hall Rally in Green Bay [FULL Video]](https://www.wisconsinrightnow.com/wp-content/uploads/2022/04/Elon_Musk_3018710552-356x220.jpg)

![The Wisconsin DOJ’s ‘Unlawful’ Lawman [WRN Voices] josh kaul](https://www.wisconsinrightnow.com/wp-content/uploads/2025/03/MixCollage-29-Mar-2025-08-48-PM-2468-356x220.jpg)

![Phil Gramm’s Letter to Wall Street Journal [Up Against the Wall]](https://www.wisconsinrightnow.com/wp-content/uploads/2025/03/gramm-356x220.png)