Susan Crawford’s rape kit attack on Brad Schimel is dishonest in many ways and blatantly ignores the wishes of survivors. Here’s how.

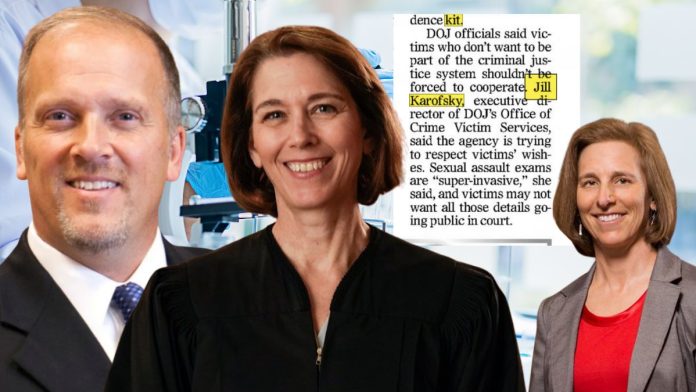

Dane County Judge Susan Crawford is slamming former Attorney General Brad Schimel for not rushing the testing of rape kits in which sexual assault survivors did not consent to the testing, rapists were already convicted or were acquitted, or the accusations were false.

Crawford, a liberal who is running against conservative Schimel for a seat on the state Supreme Court, argues he should have used taxpayer resources to test them all in two years.

Brad Schimel completed testing more than 4,100 rape kits right before leaving office in 2019 using private grants that saved taxpayers an estimated $4 million, at least, a monumental task no other AG ever accomplished. Crawford has repeatedly argued he should have rushed testing of the full 6,000, but Schimel (like Josh Kaul after him) excluded testing cases in the above categories, which no one thought was controversial until Crawford started launching political attacks. He also prioritized using taxpayer resources in the crime lab for current cases, especially where the evidence was needed in an upcoming court case or the statute of limitations was nearing.

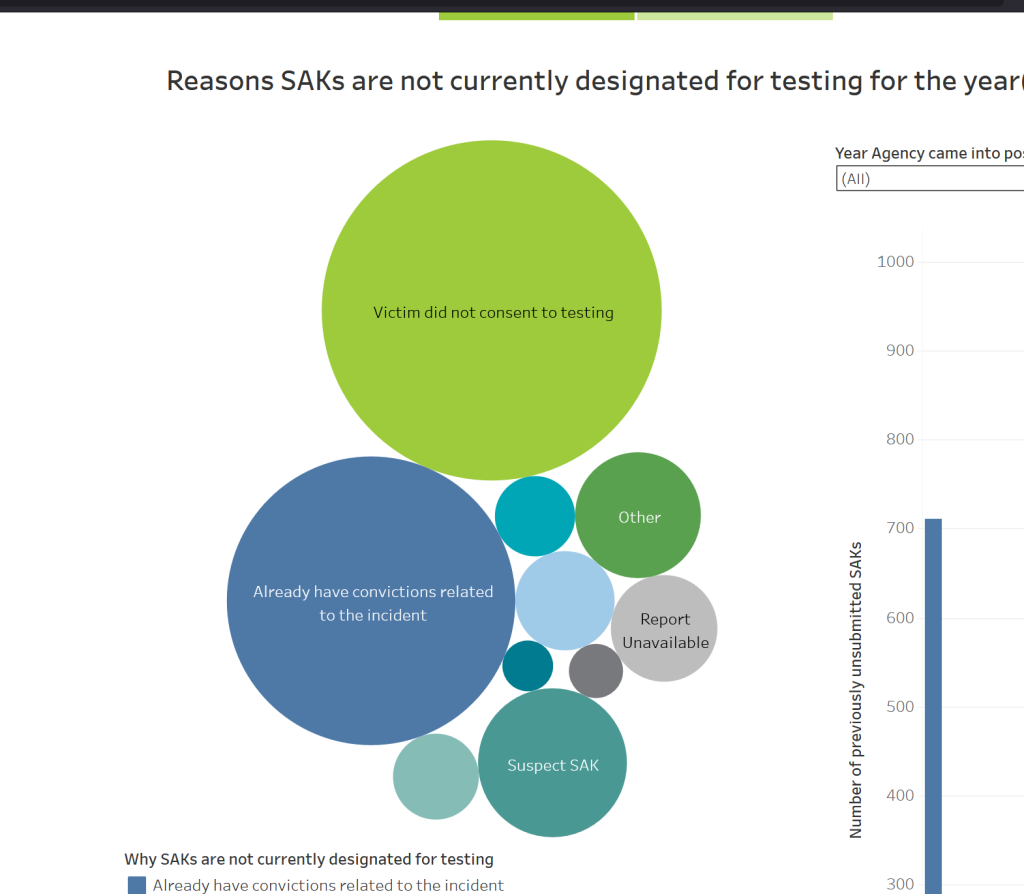

In some instances, “the victim may have initially reported the sexual assault to law enforcement, but then later decided they did not want to pursue the incident and withheld consent to test,” the Wisconsin DOJ’s Sexual Assault Kit Initiative says, in a section explaining why 35% of the 6,000 kits weren’t ever tested. “In keeping with the victim-centered approach of this project, these are currently not designated for testing.”

This was not controversial until Crawford resurrected it as a political attack. In fact, victims’ advocates stressed the importance of consent in news articles at the time.

You can’t miss the Brad Schimel rape kit angle; Crawford has made it the centerpiece of her campaign’s attacks on Schimel. “6,000 backlogged rape kits. 2 years of inaction,” Crawford wrote on her campaign X page. “Only 9 tested. Justice delayed is justice denied, and Brad Schimel has failed survivors of sexual assault at every turn.” And so it goes.

We took a deep dive into the Brad Schimel rape kit issue as a result, poring through DOJ statistics and archival newspaper stories.

Crawford has hammered Schimel relentlessly over the rape kit backlog that he inherited and fixed back in 2018. Specifically, she insists that he should have rushed through the testing of 6,000 rape kits, repeatedly using that number in political attacks. Yet thousands of those 6,000 kits fell under the aforementioned categories. In fact, in the case of acquittals, accreditation standards do not even allow testing, DOJ says.

Crawford’s statement above also ignores the fact that, during those two years, Schimel was conducting an extensive inventory of police agencies to determine how many rape kits they had, for grant purposes. The kits were sitting on police agencies’ shelves throughout the state in many cases, some of which did not cooperate. He was seeking complex federal grants, and taking other steps to shore up sexual assault protocols. These actions are documented on the DOJ’s website but also in many news articles from the time. Crawford repeated the 6,000 figure in a campaign ad.

She also ignores the fact that almost no convictions resulted from the rape kits being cleared when all was said and done. Just six people were convicted, and two of those were already in prison, according to online court records and DOJ. In one of those cases, court records say the kit wasn’t a factor in the prosecution anyway. Far from prioritizing public safety, now Attorney General Josh Kaul’s prosecutor asked for a signature bond in one case. Six other people were acquitted or had their cases dismissed, according to DOJ records.

Schimel has responded to Crawford’s attacks by saying he’s proud of his work to protect victims. He accused Crawford of lying to rape victims. It begs the question of what the decade-old rape kit controversy has to do with a seat on the state Supreme Court anyway (as opposed to, say, Crawford’s legal efforts to overturn Act 10 and Voter ID or her recent sentencing decisions going easy on child molesters); Schimel is not running for AG. But Crawford is just resurrecting a dishonest page from the partisan playbook of Josh Kaul, who flogged Schimel with the issue, narrowly defeating him in a blue-wave year with a third-party candidate on the ballot.

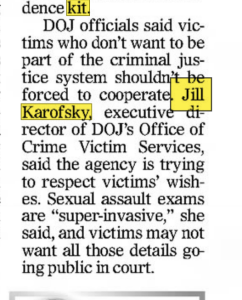

Jill Karofsky Defended Schimel’s Office

It turns out that liberal state Supreme Court Justice Jill Karofsky, who ran the Schimel DOJ’s crime victim services unit at the time, was heavily involved in the rape kit testing decisions during Schimel’s tenure, and she repeatedly defended them as being victim-centered.

Karofsky told the Associated Press in 2014, which was even before Schimel took office, that victims’ “wishes and mental well-being must come first. We’re asking them to make a huge decision. We want them to be able to control the evidence.”

In 2016, the year after Schimel took office, Karofsky told the Fond du Lac reporter that the DOJ “won’t proceed” in sending untested kits to the lab if, in the words of the Reporter, “a victim doesn’t want their kit tested.” The Reporter said Karofsky rejected calls to test all kits, saying that the “wishes of individuals who may not want to proceed with criminal charges because of privacy, health or other reasons” were important.

But now Crawford is trashing Schimel for not testing all kits – in two years.

That begs the question: If Crawford believes that the handling of the 6,000 rape kits disqualifies Schimel to sit on the state Supreme Court, why does she believe it doesn’t disqualify Karofsky?

In multiple newspaper articles at the time, Karofsky adamantly defended the Schimel DOJ’s approach to the rape kits, saying it was the right thing to do for victims. The DOJ would NOT test all kits, she told the media multiple times, because it was wrong to push forward in cases where victims did not consent. Some of her comments occurred during the two-year period that Crawford cites. Our next article will explore in depth Karofsky’s defense of Schimel’s office at the time.

After all, such kits are “super-invasive,” Karofsky said at the time, and Schimel’s DOJ believed that rape survivors shouldn’t be “forced to cooperate.”

Why does Crawford?

In 2017, after Schimel had been in office for two years, Karofsky explained what Crawford is now labeling inexcusable “inaction” by saying: “We’re trying to be careful with the kits that we’re testing. We’re testing kits where we knew victims wanted to be a part of the criminal justice system, that they’re OK doing that,” Karofsky told The Capital Times on Feb. 1, 2017. “We don’t want to test kits where we’re unsure. We want the victims to come forward.”

The DOJ was launching a public awareness campaign “aimed at connecting sexual assault survivors with their untested kits,” the article says. Back then, the news media was sensitive to this concern.

The Damaging ‘Forklift’ Approach

Karofsky and Schimel were not alone in believing that genetic material from rapes should not be tested without a victim’s consent.

The Capital Times also quoted prosecutor Audrey Skwierawski, who is now director of state courts, a position she received from the liberal justices. “The ‘forklift’ approach what Skwierawski calls the indiscriminate mass testing of old kits, has the potential to blindside and retraumatize a victim who may have never wanted her kit tested and does not want to be a part of the criminal justice system,” the Capital Times noted.

Ian Henderson, director of legal and systems services at the Wisconsin Coalition Against Sexual Assault “said a victim-centric approach is paramount,” the Capital Times reported.

Crawford’s statement could be read to imply that only 9 rape kits were ever tested, which is not true. And it’s not true that there were two years of “inaction.”

Crawford’s statement either ignorantly or willfully ignores the complexity of the federal grant process, police agencies’ slowness in responding to an inventory process (again, well-documented in the media at the time), competing resource issues at the state level (such as prioritizing crime lab resources to focus on current crimes), and the lack of probative value in many of the cases.

Overall, of the more than 6,000 kits, 4,471 rape kits were tested by November 2019, almost all in Schimel’s tenure, according to the DOJ’s website. In September 2018, Schimel announced that “evidence related to 4,154 sexual assault cases have been tested” and only five cases still needed testing. He was defeated that November. In other words, Schimel did what no AG before him had managed to do: He fixed the backlog. Democrat Josh Kaul took office a few months later.

The Capital Times says Schimel also took other actions to help sexual assault survivors. His DOJ “revised rules so victims are never billed for a forensic exam following a sexual assault. It has created a standardized form used by forensic nurses who conduct sexual assault exams statewide,” the article reported.

The state was “implementing new standards and policies for law enforcement agencies and forensic nurses statewide to ensure victims’ wishes are recorded and honored,” the Capital Times noted.

According to the DOJ, there were a few other reasons that some of the kits were never tested: the forensic material was collected during autopsies in which no rape was suspected; two consenting minors between the ages of 14 and 17 were involved; the cases weren’t chargeable because the accused was under age 12; and cases in which the suspect was acquitted; or the accusations were deemed “unfounded,” defined as, “there is credible, corroborating evidence that proves that a crime did not occur.”

Since Crawford is hammering Schimel for not testing all 6,000 kits, she should explain to the public why she thinks testing kits in the above cases would be a good use of state resources and why ignoring victims’ wishes would be the right thing to do.

The Role of Police Agencies in Rape Kit Testing

There are also good reasons that police agencies did not test many of the rape kits at the time. They were sitting on police shelves all throughout the state, a monumental effort. They weren’t all sitting in Schimel’s office. One dates back to the 1980s.

Crawford ignores this complexity, which was widely explored in the news media back then. In other words, officers made discretionary calls that testing was not needed.

The DOJ’s website lists some of those reasons. They include: the issues in the case revolved around consent, so the rape kit testing wouldn’t advance a prosecution anyway even if there was a hit (the suspect was known); police were concerned about the credibility of the victim or lack of corroboration; and the DA had already dismissed the case or hose not to pursue charges.

Jeff Twing, then a special agent with DOJ’s Division of Criminal Investigation and a former Madison police officer, told the Capital Times in 2017, “I truly believe there is a misconception of why the kits were not sent, that people weren’t doing their job.” He said there were numerous cases where he didn’t send a kit for testing during his career because it “does not help the investigation or affect the charging decision in the case.”

An Appleton Post-Crescent article also quoted Twing in 2018. It described the monumental efforts the Schimel DOJ was taking to get the kits counted. The article says Twing, who worked for Schimel’s agency, repeatedly contacted one sheriff’s office that wasn’t responding and even offered to drive hours to count them himself.

The grant rules said that “the state couldn’t use grant money to pay for testing those kits until every police and sheriff’s department in Wisconsin inventoried them.” The article cites “police neglect” for delaying testing, saying that more than 300 departments “failed to complete inventories even after they were given an extended deadline.”

Schimel got special approval from the federal government in October 2016 to begin tests while “tardy inventories rolled in,” the article says. Yet, clearing the backlog took some time because of capacity in labs that were also dealing with a nationwide glut because of news coverage by USA Today.

“Wisconsin’s first contract went to a Virginia-based company that said it could analyze up to 200 kits a month,” the article said. Schimel then contracted with two other labs.

Crawford’s attacks ignore all of this reality and complexity. She acts like Schimel could have snapped his fingers and tested 6,000 kits overnight and even that he should have in the cases where victims didn’t desire it.

“In November 2016, grantors certified the first phase of Wisconsin’s previously unsubmitted sexual assault kits, and DOJ was permitted to initiate testing, including sending 200 sexual assault kits per month to Bode Cellmark Forensics,” DOJ wrote at the time, explaining the process.

“DOJ has continually monitored the capacity of labs in the nation, and in 2017, DOJ was awarded supplemental grants from the U.S. Bureau of Justice Assistance (BJA), which allowed DOJ to contract with Sorenson Forensics, in Salt Lake City, Utah and Marshall University Forensics Science Center, in Huntington, West Virginia to test WiSAKI kits, which began in January 2018. Sorenson has contracted to test 1,000 kits, and Marshall University will test 300 kits by the end of 2018.”

A July 17, 2015, article by Keegan Kyle for Gannett Wisconsin Media Team says that some police agencies didn’t forward the kits for testing because they were “categorized as false complaints when victims recanted.”

The state survey “required tedious clerical work, sorting through scores of boxes in refrigerators and reading investigator notes from more than a decade ago,” according to the article. At first, one-third of agencies didn’t even respond.

A 2017 article in the Green Bay Press-Gazette also documented this point. That article says that police agencies told the newspaper that there were “several reasons for having untested kits in their evidence rooms,” including survivors not wanting to press charges or kits being stored even after an offender was “released from prison” and convicted.

Furthermore, according to the article, cases with “an urgent court deadline are supposed to be tested first” at the State Crime Lab, followed by cases “nearing a statute of limitations.”

“If a victim wants to participate in the criminal justice system, we’re going to test those kits,” Karofsky said in that article. “For someone who’s already been the victim of a horrible crime, we don’t put the world on their shoulders. It’s too much to ask if they’re unable to do it.”

The entire controversy ignited months BEFORE Schimel was even elected due to a USA Today investigation that documented the number of untested rape kits nationwide. In other words, this also was not unusual. And, frankly, there were good reasons for it. Yet the news media at the time was locked into narratives painting law enforcement as somehow nefarious rather than seeing there was a good reason for a lot of the lack of testing.

Weeks later, the U.S. Department of Justice offered Wisconsin “$2 million for testing and an additional $2 million for investigative work, research, and a public awareness campaign,” according to a 2016 article in the Fond du Lac Reporter.

That article quotes Schimel as saying, “This money will go a long way to bring justice to survivors of sexual assault.” The DOJ in Wisconsin was surveying “untested rape kits” to see which police agencies were holding them, the article says.

A Justice Department spokesman said then, “There is not a delay. This process takes time,” adding, “Conducting a detailed statewide inventory is a long and arduous process, especially if you do it the right way.” In 2016, Schimel’s DOJ sent out a survey to more than 575 agencies, the article says, and was seeking “approval from grant authorities to start testing some kits while the process continues.”

Karofsky noted in that article that the survey could be a “demanding project at small, rural agencies with stretched staffing” who had “paper-based systems to manage evidence.’

Many of the 4,471 kits that were ultimately tested fell under these categories. Under enormous media and political pressure (started by a reporter who is now an investigative editor for the very liberal Capital Times), Schimel obtained outside funding to clear them anyway, saving the state at least $4 million.

Susan Crawford Argues That State Tax Dollars Should Have Been Used

Crawford believes Schimel should have completed such testing sooner at a cost to taxpayers of $1,000 per kit. She told the Green Bay Press-Gazette as much on the campaign trail, trashing Schimel for seeking “arduous” grants instead of demanding that state lawmakers fork over additional tax dollars to perform the task instead.

However, Crawford ignores the practical reality that the Attorney General must balance competing needs; for example, Schimel chose to prioritize state funding and crime lab positions toward then-current homicide and rape cases, rather than delay those cases, which did have probative value and active suspects, by clogging the crime lab with the glut of old kits. In addition, Schimel did not believe it made sense to create new state taxpayer-funded positions for a one-time project, newspaper articles at the time say; in other words, once the backlog was cleared, they would not be needed.

However, Crawford ignores the practical reality that the Attorney General must balance competing needs; for example, Schimel chose to prioritize state funding and crime lab positions toward then-current homicide and rape cases, rather than delay those cases, which did have probative value and active suspects, by clogging the crime lab with the glut of old kits. In addition, Schimel did not believe it made sense to create new state taxpayer-funded positions for a one-time project, newspaper articles at the time say; in other words, once the backlog was cleared, they would not be needed.

Considering the result of the entire process (only six convictions), it’s hard to argue with this decision.

Thus, it’s hard to see why it would have been a smart use of resources for Schimel to reprioritize old rape kits (some dating back decades) that police agencies all over the state didn’t believe had probative value, over the testing of current rapes, homicides, and other violent crimes. Instead, Schimel sought federal grants, which was a laborious and time-consuming process, but it ultimately got the job done without disrupting the crime lab’s ability to handle new cases.

Schimel’s crime lab routinely reported faster turn-around times while handling far more cases during his tenure than AG Josh Kaul’s has. This might be one reason why.

“WiSAKI’s unique, victim-centered approach involved an individual assessment of each of the 6,000+ SAKs held by law enforcement agencies and hospitals in Wisconsin,” DOJ’s website says.

“Due to the complexity of this inventory process and a commitment to accuracy, Wisconsin Department of Justice (DOJ) personnel and local law enforcement agencies divided the state into regions and worked with agencies to document each individual SAK. Law enforcement agencies statewide willingly collaborated with DOJ in this effort. For more information on this process see the Inventory Collection Methodology.”

Table of Contents

![WATCH: Elon Musk Town Hall Rally in Green Bay [FULL Video]](https://www.wisconsinrightnow.com/wp-content/uploads/2022/04/Elon_Musk_3018710552-356x220.jpg)

![The Wisconsin DOJ’s ‘Unlawful’ Lawman [WRN Voices] josh kaul](https://www.wisconsinrightnow.com/wp-content/uploads/2025/03/MixCollage-29-Mar-2025-08-48-PM-2468-356x220.jpg)