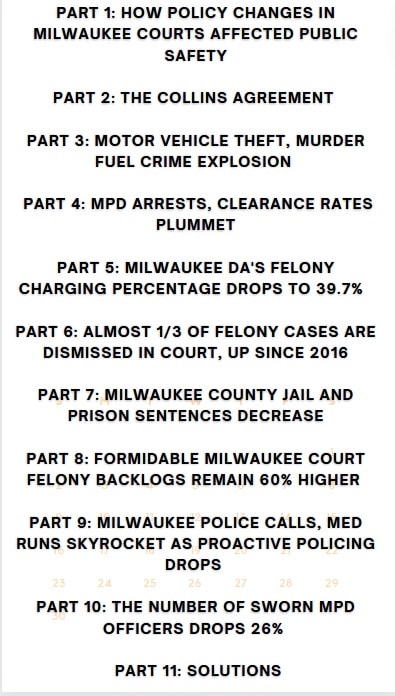

PART TWO IN AN 11-PART SERIES. See part 1 here.

Milwaukee County’s criminal justice system has broken down at almost all levels.

Although some of the breakdown can be attributed to the pandemic, some can not. Local officials’ questionable policy decisions also play a role, and it’s imperiling public safety. The pandemic exacerbated some already existing trends and caused others, but officials have not developed effective strategies to recover. Some non-pandemic-related issues, like the ACLU-related Collins Agreement’s impact on proactive policing and plummeting numbers of police officers (down 26% since 1996) have been largely overlooked in the media.

PROBLEM #2: The Collins Agreement & Decline in Proactive Policing

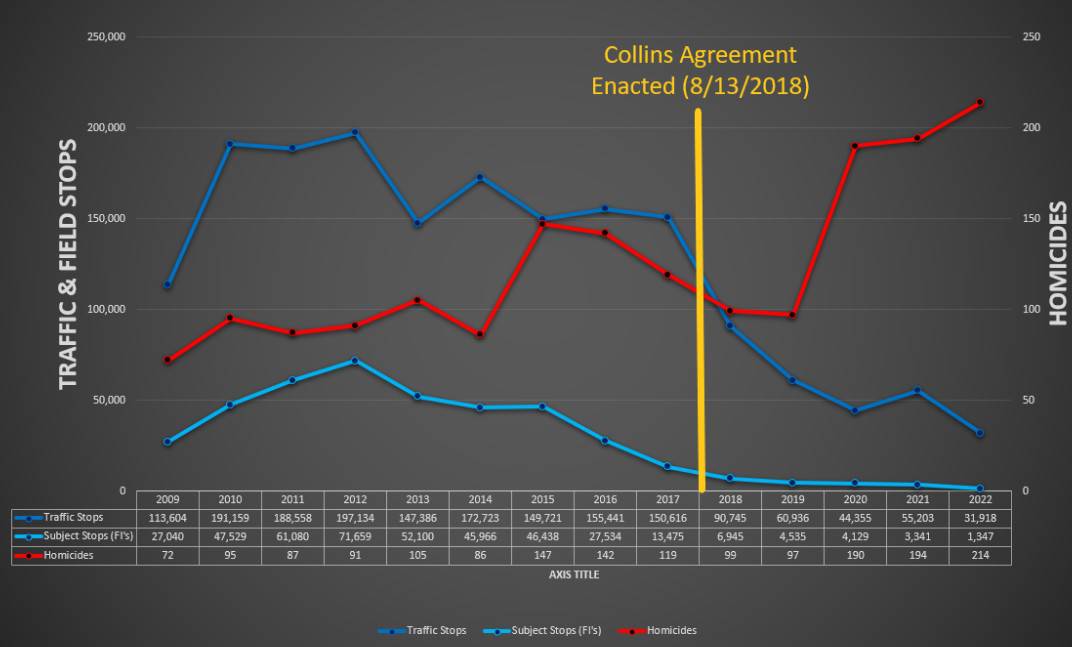

A key legal settlement affected policing in Milwaukee well before the pandemic was even a thought. In 2018, the City of Milwaukee entered into a settlement known as the “Collins Agreement,” that many Milwaukee police officers say destroyed proactive policing in the city, driving down the number of traffic stops and field interviews to a near halt. This ACLU-driven lawsuit alleged racial discrimination in traffic stops.

Although dispatched calls for service rose 7% from 2018 to 2022, proactive policing activities declined 59%, a new report documents. This reduction in proactive policing is not only the result of the Collins Agreement (in part 9, we will explore how an increase in police med runs and calls for service has also distracted MPD officers from proactive policing. In part 10, we will discuss the sharp drop in the number of Milwaukee police officers since 1996.)

We previously interviewed current and retired Milwaukee police officers who, in the strongest of terms, slammed the Collins Agreement for destroying proactive policing in Milwaukee through its cumbersome and, they believe, punitive, requirements. The drop in field interviews, arrests, and traffic stops since the Collins Agreement has been very dramatic. For example, field interviews dropped 90%, from 71,659 in 2012 to just 41 for December 2022. Arrests have plummeted.

Retired and current Milwaukee police officers described a nightmarish scenario of retribution, plummeting morale, and stifling rules that have all but stalled proactive policing in the city.

“Why be the only variable in the broken justice system who cares, only to our own personal detriment? I’m just counting the days to retirement. Then they can pay me to stay away until I die,” one MPD officer, upset about the Collins Agreement, told us.

“I used to be very proactive,” another officer told us. “Now, I act like a fireman. I sit and wait for a call, go take that call, then go back to waiting for the next call. I, and most cops, no longer do ANY proactive policing.”

We have taken the lead in exploring the problems in Milwaukee County’s Criminal Justice system since our site launched in 2020, breaking stories on Milwaukee police staffing declines (which started years ago), the DA’s high non-prosecution rate and new reliance on summonses, the 2018 ACLU Collins Agreement’s deleterious effect on proactive policing, new jail and police policies restricting bookings and arrests, and the massive court backlogs, which leave defendants on the streets longer to re-offend and provoke constitutional concerns. Milwaukee is at a crisis point, with record homicide numbers and a severe reckless driving crisis.

Now, a new August 2023 report from the Wisconsin Policy Forum has examined Milwaukee County’s Criminal Justice System in great detail, providing fresh data from 2018 (before the pandemic) to 2022. We are excerpting some of the key statistical findings in our 11-part series to further understanding of the problem. You can’t formulate solutions if you don’t understand the problem’s scope. The few news articles that emerged only superficially skimmed over the report’s findings. The report’s authors are Rob Henken, Ari Brown, and Betsy Mueller.

Although the report deals with the context of the pandemic, it also makes it clear that, in some respects, trends imperiling public safety started before it or have continued, even escalating in some cases, in 2022, after its height. In other words, you can’t blame everything on the pandemic. The report also indicates that, in a number of ways, some problems that escalated during the pandemic have not been resolved by officials even as late as 2022. In other cases, progress has been made.

“Overall, this report has revealed that multiple key points of the justice system pipeline in Milwaukee County are not functioning in the same way or at the same level as they were prior to the pandemic,” the authors wrote. “It is now incumbent upon justice system leaders and state and local policymakers to aggressively explore why that is, to what degree it may have impacted public safety, what progress is being made in remedying the identified challenges, and whether additional resources or other solutions are required to get the system back on track.”

In each article, which we will run over the next 11 days at 7 a.m. every day, we will outline the problems and present the research. After that, we will run a wrap-up article suggesting solutions. What happens in the state’s largest county has an effect throughout Wisconsin. The WPF report was commissioned by the Milwaukee-based Argosy Foundation and the Milwaukee Community Justice Council (CJC). Most of it is focused on useful data. In cases where we think aspects were left out, we will note that. In this series, we hope to get past simplistic rhetoric (“it’s the state Legislature’s fault!” on the left or “who cares what happens in Milwaukee!” on the right.)

PROBLEM #2: The ACLU-fueled Collins Agreement

We were happy to see that the new report discussed the Collins Agreement in its analysis of the criminal justice system in Milwaukee County. The new report notes that every issue in the criminal justice system was not driven by the pandemic, and it does raise the question of whether the Collins Agreement negatively affected the functioning of the criminal justice system and reduced officers’ interactions with alleged offenders on the streets.

This is a welcome finding as, until now, the effect of the Collins Agreement on policing and public safety in Milwaukee has largely been ignored by the media and policymakers, who have tended to focus on Collins Agreement oversight reports finding that all of the Collins Agreement requirements are still not being met by MPD (putting pressure on police to embrace it MORE) rather than analyzing how those requirements may be imperiling public safety. We would encourage additional study of the Collins Agreement’s effect on proactive policing to include the voices of police officers who are on the streets dealing with it every day.

“Several additional important environmental factors occurred prior to and during the pandemic that undoubtedly have impacted the functioning of the justice system,” the report says in a section called, “Collins Settlement Impacted Police Practices in Milwaukee.”

As background, the report explains that, in February 2017, a group of people sued the City of Milwaukee, its Fire and Police Commission, and the Milwaukee Police Department’s chief on “alleged grounds that MPD’s policies and procedures related to stops and frisks lacked reasonable suspicion and were racially motivated and thus were unconstitutional.” The city entered a settlement agreement, known as the Collins Agreement, in July 2018, which required the MPD and Fire and Police Commission to make changes “relating to stop and frisk policies, documentation, training and oversight and public transparency.”

“These changes included amendments to several MPD Standard Operating Procedures (SOPs) to ensure enhanced documentation and justification in areas like citizen contacts, field interviews, searches and seizures, practices regarding video and audio equipment and body cameras, and inspections,” the report says.

“MPD also agreed to rescind and replace its traffic enforcement policy and was prohibited from using data related to numbers of traffic stops, field interviews, frisks, and other encounters for performance evaluation purposes. The overall intention, as stated in the agreement, was to ensure that police encounters in Milwaukee “are supported by individualized, objective, and articulable reasonable suspicion.”

The report notes:

- Although dispatched calls for service rose 7% from 2018 to 2022, proactive policing activities declined 59%.

- “Legal and external factors may have created an environment in which MPD officers interact less frequently with individuals who may have engaged in criminal behavior,” listing the Collins Agreement as an example.

- Some interviewees outside of the department suggested to the report’s authors that both the 2017 “Collins Agreement” and “the public outcry and demonstrations following the murder of George Floyd and other high-profile police incidents” had possibly “contributed to a change in the way Milwaukee police officers are carrying out their duties on the street.” They noted that no data exists to confirm or debunk this belief. We would note that multiple data points do show a plummeting drop in arrests, field interviews, and traffic stops, dating to the Collins Agreement settlement year, although the cause can be debated and is probably not limited to a single factor.

- That Collins settlement “as well as the highly increased scrutiny of all police actions in the wake of the Floyd tragedy was cited by some of our interviewees as potentially having reduced the inclination of officers to formally encounter individuals, thus reducing the number of arrests that once would have resulted from such encounters and also limiting their contacts with potential witnesses and informants,” the report says, while noting that there is not data to prove or debunk this hypothesis.

- “It is possible that changes in the department’s leadership during the study period may have contributed as much or more than these other environmental factors to some of the data trends we have outlined, though again such a hypothesis is only speculative,” the report says.

- The discussion about the Collins Agreement comes in a section on plummeting arrests in Milwaukee, a trend that started before the pandemic. We will discuss that plunge in arrests in great detail in part 4.

- “Arrests in the city of Milwaukee began to plummet even before the pandemic and have continued their descent since that time. In 2022, arrests were 36.8% lower for Part 1 crimes and 61.0% lower for Part 2 crimes in the city than in 2018,” the report says.

- “One of our most striking findings in this report is the sharp (-61.0%) decline in Part 2 arrests in the city of Milwaukee from 2018 to 2022, despite the 26.4% increase in Part 2 offenses,” the report says (note that 2018 is the year the Collins Agreement went into effect).

The report does not quote individual Milwaukee police officers on their views of the Collins Agreement’s effect. We did, so we would strongly encourage you to read our report on the Collins Agreement here. In it, we note:

- Since the 2017 ACLU lawsuit that resulted in the Collins Agreement against the Milwaukee Police Department, field interviews conducted by Milwaukee police officers have decreased 90%.

- Since 2012, the year after a Milwaukee Journal Sentinel expose started putting the pressure on by implying police were racist, field interviews, also known as “subject stops,” plummeted a shocking 98%.

- Field interviews are now so rare that MPD only did 41 of them in December 2022. In 2012, MPD conducted 71,659 field interviews.

- Traffic stops decreased 79% since the ACLU lawsuit against MPD. Reckless driving exploded.

- “The ACLU (Collins Agreement) has destroyed proactivity within the department, which the crime stats show in my opinion,” a former MPD officer told WRN. “I now work in a suburban department out of Milwaukee County, and let me say it’s a night-and-day difference. We get to be police officers and catch the bad guys.”

- Another officer told us: “The citizens of Milwaukee would be blown away by the amount of time police officers are spending behind computer screens dealing with these Collins’ related forms (which are redundant anyways) and not being the watchmen (and watchwomen) they need.”

- And yet another officer said: “Violent crime has grown dramatically since the Collins Agreement, and we are scrutinized more drastically. Why can’t we search a car that has the odor of fresh marijuana? Why couldn’t we in prior years pull over cars for not being registered? Why is it an SOP that we cannot pursue a stolen vehicle if we know it is being driven by a juvenile? – which is a large reason the Kia kids exist. How come when we arrest Kia kids, they are out of custody the same day? Why are we arresting the same kid for stealing cars 5 or 10 times?”

Read tomorrow’s article exploring rising crime numbers in Milwaukee County.

Table of Contents