PART 8 N AN 11-PART SERIES. Read parts 1, 2, 3, 4, 5, 6 and 7.

Milwaukee County’s criminal justice system has broken down at almost all levels.

Although some of the breakdown can be attributed to the pandemic, some can not. Local officials’ questionable policy decisions also play a role, and it’s imperiling public safety. The pandemic exacerbated some already existing trends and caused others, but officials have not developed effective strategies to recover. Some non-pandemic-related issues, like the ACLU-related Collins Agreement’s impact on proactive policing and plummeting numbers of police officers (down 26% since 1996) have been largely overlooked in the media.

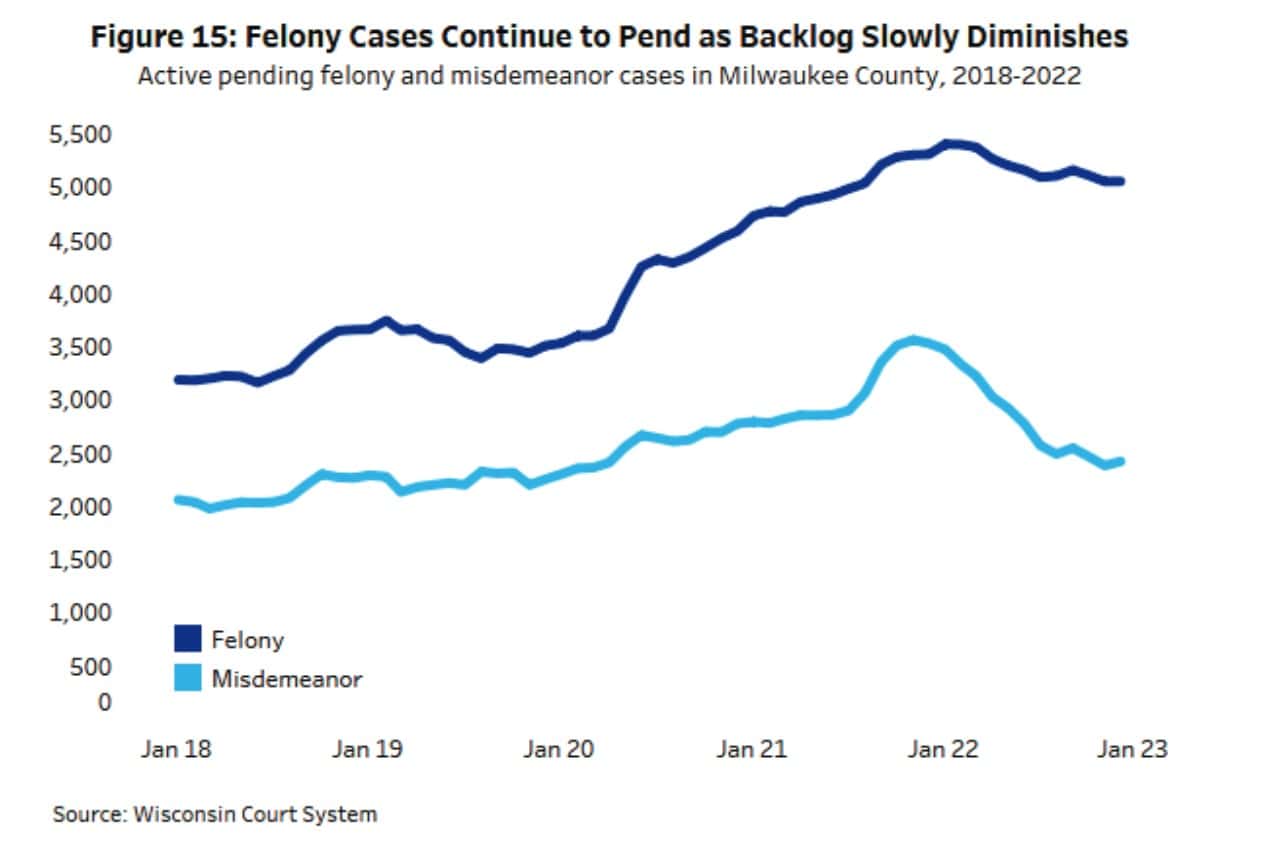

PROBLEM #8: Milwaukee court backlogs have not been resolved. Felony case backlogs remain severe in the Milwaukee County court system. In December 2022, there were 5,056 pending cases, 59.8% higher than before the pandemic. They “had yet to be meaningfully reduced as of the end of last year.” The felony backlog remains “formidable.”

To gauge backlogs in the court system, disposition data (how long it takes to resolve a case) are important. Backlogs are created when dispositions plunge and the number of cases filed and opened remains largely consistent.

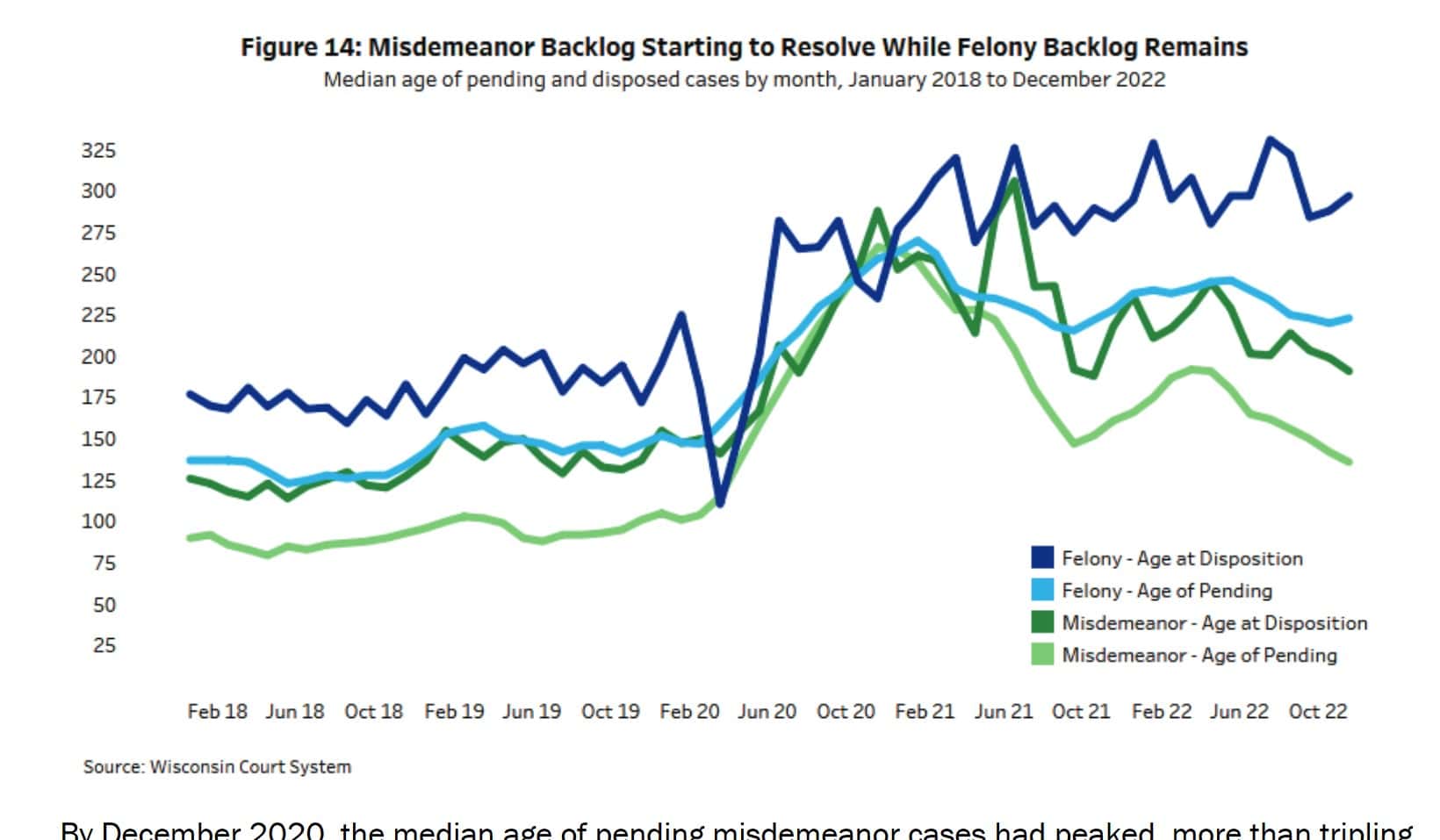

The median age of pending cases increased significantly during the pandemic and has not fully recovered. In mid-2018, the median age of pending felony cases was a low of 123 days in June and the median age of misdemeanor cases reached a low of 79.5 days in May. Both increased at the onset of the pandemic. By December 2020, the median age for both felonies and misdemeanors had almost tripled.

Since that time, “both have fallen but remain significantly above their pre-pandemic lows: in December 2022, at 218 days, the median age of pending felony cases was 77.2% above the pre-pandemic low, and the median age of pending misdemeanor cases was similarly 76.1% above its low point.”

The amount of time it took to dispose of a misdemeanor case in 2022 is still higher than before the pandemic – 186 days. Felony cases are taking longer to dispose of – 289 days, up from 150-200 in 2018-2020.

As for the number of cases pending (another measure of backlog), misdemeanor cases have returned to pre-pandemic levels.

Backlogs lead to more cases being dismissed as witnesses can’t be located anymore and defendants don’t plead guilty because they know the longer the case pends, the more likely it might be dismissed.

THE SERIES:

THE SERIES:

We have taken the lead in exploring the problems in Milwaukee County’s Criminal Justice system since our site launched in 2020, breaking stories on Milwaukee police staffing declines (which started years ago), the DA’s high non-prosecution rate and new reliance on summonses, the 2018 ACLU Collins Agreement’s deleterious effect on proactive policing, new jail and police policies restricting bookings and arrests, and the massive court backlogs, which leave defendants on the streets longer to re-offend and provoke constitutional concerns. Milwaukee is at a crisis point, with record homicide numbers and a severe reckless driving crisis.

Now, a new August 2023 report from the Wisconsin Policy Forum has examined Milwaukee County’s Criminal Justice System in great detail, providing fresh data from 2018 (before the pandemic) to 2022. We are excerpting some of the key statistical findings in our 11-part series to further understanding of the problem. You can’t formulate solutions if you don’t understand the problem’s scope. The few news articles that emerged only superficially skimmed over the report’s findings. The report’s authors are Rob Henken, Ari Brown, and Betsy Mueller.

Although the report deals with the context of the pandemic, it also makes it clear that, in some respects, trends imperiling public safety started before it or have continued, even escalating in some cases, in 2022, after its height. In other words, you can’t blame everything on the pandemic. The report also indicates that, in a number of ways, some problems that escalated during the pandemic have not been resolved by officials even as late as 2022. In other cases, progress has been made.

“Overall, this report has revealed that multiple key points of the justice system pipeline in Milwaukee County are not functioning in the same way or at the same level as they were prior to the pandemic,” the authors wrote. “It is now incumbent upon justice system leaders and state and local policymakers to aggressively explore why that is, to what degree it may have impacted public safety, what progress is being made in remedying the identified challenges, and whether additional resources or other solutions are required to get the system back on track.”

In each article, which we will run over the next 11 days at 7 a.m. every day, we will outline the problems and present the research. After that, we will run a wrap-up article suggesting solutions. What happens in the state’s largest county has an effect throughout Wisconsin. The WPF report was commissioned by the Milwaukee-based Argosy Foundation and the Milwaukee Community Justice Council (CJC). Most of it is focused on useful data. In cases where we think aspects were left out, we will note that. In this series, we hope to get past simplistic rhetoric (“it’s the state Legislature’s fault!” on the left or “who cares what happens in Milwaukee!” on the right.)

PROBLEM #8

The report found: “Sizable backlogs in cases pending before the courts understandably emerged during the peak months of the pandemic and have now largely been erased for misdemeanors. However, the felony backlog had budged only slightly by the end of 2022 despite decreases in felony arrests and charges and increases in felony dismissals.”

The report noted that the DA’s office had cited that “because cases are taking much longer to resolve, there is a much higher likelihood of dismissal, as there is a greater chance that witnesses cannot be located and that other factors will transpire that will impede the ability of prosecutors to support charges or that will cause complainants to settle or drop their cases (DA office officials say this may be particularly the case for domestic violence-related cases). Similarly, they suggested that defense attorneys are now more inclined to urge clients not to plead guilty knowing that the case will linger and the odds of dismissal will rise as it does so.”

The report noted: “Justice system officials have cited staffing shortages in positions ranging from court reporters to district attorneys to public defenders as a primary cause of sustained backlogs.”

Furthermore, “an explosion in evidence from video cameras, cell phones, and computers” takes more time for cases to be investigated, defended and prosecuted, the report says. They also said that, since the pandemic, the courts have seen an “increased number of individuals in the system who suffer from behavioral health disorders.” Competency examinations rose 32%.

Backlogs

- “In mid-2018, the median age of pending felony cases reached a low of 123 days in June and the median age of misdemeanor cases reached a low of 79.5 days in May. However, both began to increase significantly at the onset of the pandemic.”

- “By December 2020, the median age of pending misdemeanor cases had peaked, more than tripling to 266 days; while by February 2021, the median age of pending felony cases had done the same, more than doubling to 270 days.”

- “Since that time, both have fallen but remain significantly above their pre-pandemic lows: in December 2022, at 218 days, the median age of pending felony cases was 77.2% above the pre-pandemic low, and the median age of pending misdemeanor cases was similarly 76.1% above its low point.”

- “These data indicate that while disposition numbers are now close to pre-pandemic levels, the two years in which the pandemic reduced the number of dispositions has caused cases to linger far longer than prior to the pandemic.”

- “Another metric that sheds light on that point is the average amount of time it takes to dispose of a case (this differs from the age of pending cases in that it measures disposition time from start to finish as opposed to average time of cases pending at a specific point in time). The median age of a misdemeanor case at disposition ranged from about 120 to 150 days prior to the pandemic but started rising significantly at the pandemic’s height, hitting a peak of 306 days in July 2021. As of December 2022, that number had fallen back to 186 days, however.”

- “Felony cases tell a different story. The median age of a felony case at disposition from January 2018 until the beginning of the pandemic generally ranged from 150 to 200 days. As with misdemeanor cases, the median age began rising in early 2020, but it did not peak until August 2022 when it hit 331 days, and it has been above 250 days in every month since the start of 2021. In fact, the median age of a disposed felony case in December 2022 (289 days) was higher than in any month from the start of 2018 until February 2021.”

- “Prior to the pandemic, 1,900 to 2,400 misdemeanor cases were pending in any given month; that rose to a peak of 3,566 by November 2021. Since that time, the misdemeanor pending caseload has returned to pre-pandemic levels, as the number of pending misdemeanor cases in December 2022 (2,424) was very similar to the number of cases when the pandemic commenced.”

- “Here, felony cases again tell a different story. The number of pending felony cases

generally ranged from 3,100 to 3,800 in 2018 and 2019 and then rose slowly for

nearly two years starting at the beginning of the pandemic, peaking at 5,405 in January

2022. Since that time, they have started to drop, but the 5,056 pending cases in December 2022 were just 6.5% lower than the pending case peak and 59.8% higher than the pre-pandemic low of 3,163 cases.”

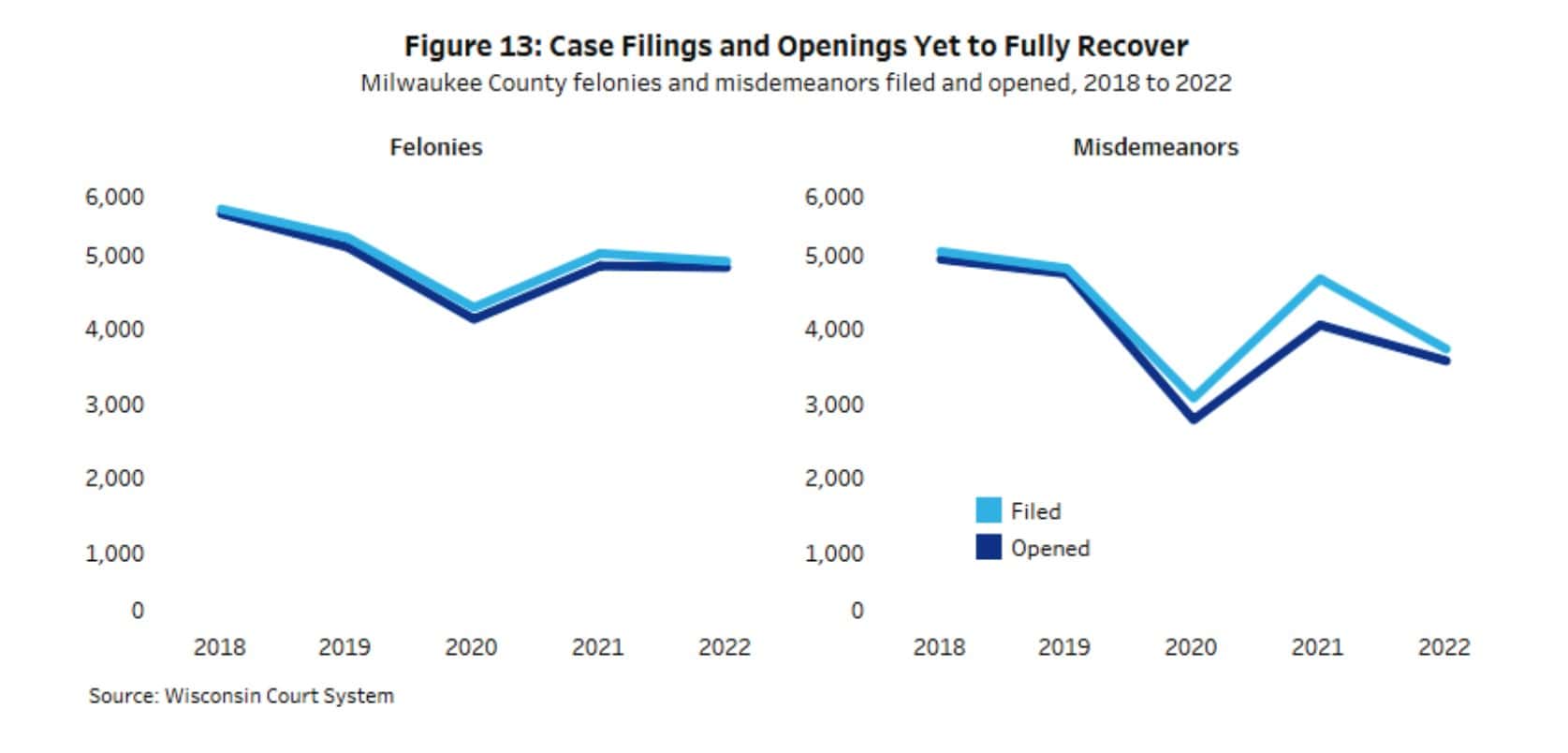

Case filings are down

“Case filings reflect all criminal complaints submitted by the district attorney to the Circuit Court. Sometimes – but not often – cases may be dismissed prior to being opened,” the report says.

The report found:

- “The data show that total case filings were down significantly in 2020 – more than 12,300 cases were filed in both 2018 and 2019 before a decline to just 8,447 in 2020. While case filings rose in 2021 to 11,314, they again dropped to 9,484 in 2022.”

- “Felony case filings have recovered the most of any individual category, as shown in Figure 13 – the 4,907 felony cases filed in 2022 were just 6.1% below the 5,226 filed in 2019, and 14.4% above the number filed in 2020. Misdemeanor filings fell from 2019 to 2020, rebounded in 2021, but dropped again in 2022 to 22.4% below 2019 levels.”

- “More than three-fifths of all months from January 2018 to February 2020 saw at least 400 misdemeanor cases filed; since the beginning of the pandemic, however, there have been just three months in which at least that many cases were filed.”

- “For both felonies and misdemeanors, the drop in case filings in 2022 appears to be linked, at least in part, to the far fewer numbers of arrests and charges discussed in earlier sections.”

Table of Contents

![WATCH: Elon Musk Town Hall Rally in Green Bay [FULL Video]](https://www.wisconsinrightnow.com/wp-content/uploads/2022/04/Elon_Musk_3018710552-265x198.jpg)

![The Great American Company [Up Against the Wall]](https://www.wisconsinrightnow.com/wp-content/uploads/2025/03/MixCollage-29-Mar-2025-09-08-PM-4504-265x198.jpg)

![The Wisconsin DOJ’s ‘Unlawful’ Lawman [WRN Voices] josh kaul](https://www.wisconsinrightnow.com/wp-content/uploads/2025/03/MixCollage-29-Mar-2025-08-48-PM-2468-265x198.jpg)