PART ONE IN AN 11-PART SERIES

Milwaukee County’s criminal justice system has broken down at almost all levels.

Although some of the breakdown can be attributed to the pandemic, some can not. Local officials’ questionable policy decisions also play a role, and it’s imperiling public safety. The pandemic exacerbated some already existing trends and caused others, but officials have not developed effective strategies to recover. Some non-pandemic-related issues, like the ACLU-related Collins Agreement’s impact on proactive policing and plummeting numbers of police officers (down 26% since 1996) have been largely overlooked in the media.

PROBLEM #1: The first problem IS related to the pandemic, but, more specifically, officials’ reaction to it. Officials in the Milwaukee County criminal justice system and at Tony Evers’ Department of Corrections made a series of policy changes responding to the COVID-19 pandemic that fueled a lack of offender accountability, slowed down the criminal justice process, and kept more defendants, including repeat criminals, out of custody longer and with less pretrial supervision, leaving some free to re-offend.

These decisions ranged from suspending drug testing for people out on bail, suspending risk assessment of people booked into the jail who are subject to bail, and initially reducing the number of courtrooms from 21 to three. From Milwaukee County Chief Judge Mary Triggiano to DA John Chisholm, a series of policy decisions altered public safety in Wisconsin’s most populous county.

These decisions ranged from suspending drug testing for people out on bail, suspending risk assessment of people booked into the jail who are subject to bail, and initially reducing the number of courtrooms from 21 to three. From Milwaukee County Chief Judge Mary Triggiano to DA John Chisholm, a series of policy decisions altered public safety in Wisconsin’s most populous county.

[Note: In 2021, we analyzed Milwaukee County medical examiner data to reveal that 96.4% of people listed as COVID deaths had other serious health problems. The response to COVID, although it was happening in real time where much was not yet known, was ultimately a judgment call on how to balance competing harms/perceived harms. A balance needed to be struck between COVID-19 concerns and the harm caused to public safety by reducing accountability for accused criminals and imperiling the court system’s ability to function effectively. It seems increasingly clear that the latter harm was significant. It has not received enough attention, including whether the system took too long to roll back policies installed during COVID-19’s height.]

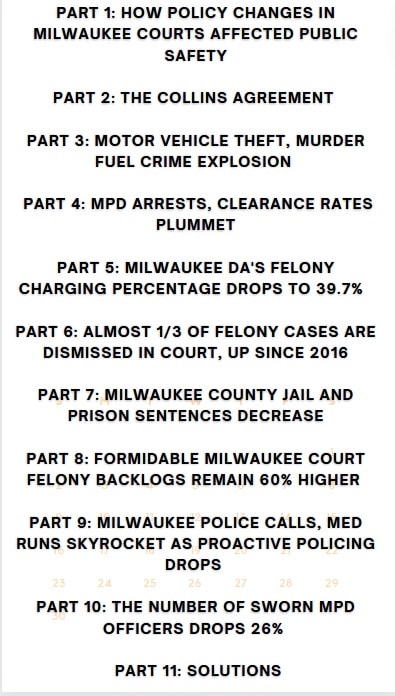

THE SERIES:

THE SERIES:

We have taken the lead in exploring the problems in Milwaukee County’s Criminal Justice system since our site launched in 2020, breaking stories on Milwaukee police staffing declines (which started years ago), the DA’s high non-prosecution rate and new reliance on summonses, the 2018 ACLU Collins Agreement’s deleterious effect on proactive policing, new jail and police policies restricting bookings and arrests, and the massive court backlogs, which leave defendants on the streets longer to re-offend and provoke constitutional concerns. Milwaukee is at a crisis point, with record homicide numbers and a severe reckless driving crisis.

Now, a new August 2023 report from the Wisconsin Policy Forum has examined Milwaukee County’s Criminal Justice System in great detail, providing fresh data from 2018 (before the pandemic) to 2022. We are excerpting some of the key statistical findings in our 11-part series to further understanding of the problem. You can’t formulate solutions if you don’t understand the problem’s scope. The few news articles that emerged only superficially skimmed over the report’s findings. The report’s authors are Rob Henken, Ari Brown, and Betsy Mueller.

Although the report deals with the context of the pandemic, it also makes it clear that, in some respects, trends imperiling public safety started before it or have continued, even escalating in some cases, in 2022, after its height. In other words, you can’t blame everything on the pandemic. The report also indicates that, in a number of ways, some problems that escalated during the pandemic have not been resolved by officials even as late as 2022. In other cases, progress has been made.

“Overall, this report has revealed that multiple key points of the justice system pipeline in Milwaukee County are not functioning in the same way or at the same level as they were prior to the pandemic,” the authors wrote. “It is now incumbent upon justice system leaders and state and local policymakers to aggressively explore why that is, to what degree it may have impacted public safety, what progress is being made in remedying the identified challenges, and whether additional resources or other solutions are required to get the system back on track.”

In each article, which we will run over the next 11 days at 7 a.m. every day, we will outline the problems and present the research. After that, we will run a wrap-up article suggesting solutions. What happens in the state’s largest county has an effect throughout Wisconsin. The WPF report was commissioned by the Milwaukee-based Argosy Foundation and the Milwaukee Community Justice Council (CJC). Most of it is focused on useful data. In cases, where we think aspects were left out, we will note that. In this series, we hope to get past simplistic rhetoric (“it’s the state Legislature’s fault!” on the left or “who cares what happens in Milwaukee!” on the right.)

PROBLEM #1: Policy changes that affected safety

As the COVID-19 pandemic hit, criminal justice leaders in Milwaukee County and the state made a series of policy changes that had a dramatic impact on the criminal justice system in Milwaukee County.

The Wisconsin Policy Forum report provides an exhaustive detailing of these policy decisions. It does not take a stance on whether they were necessary or went too far. The conclusion that they imperiled public safety in the headline is our own. Beyond that, we are going to keep rhetoric out of this section as well and leave that to you, the readers, and to the solutions article. In this section, we want to tell you factually what occurred. Some of it was known before; other decisions have flown beneath the radar.

According to the report, these changes included:

- suspension of universal screening interviews for people booked into the jail until September 2021 (and a month in 2022). “Pretrial risk assessment, or screening, is conducted on all individuals booked into the CJF who are subject to bail. The assessment provides stakeholders with information to further inform their bail decisions. The screening interview is voluntary and preliminarily identifies individuals who may be eligible for early intervention programming (e.g. diversion, deferred prosecution, or treatment court),” it says;

- suspension of drug testing as a condition of bond for people on pretrial supervision (the report also notes that Milwaukee County has seen “a continued rise in drug deaths in Milwaukee County (from 419 in 2019 to 544 in 2020, 644 in 2021, and 650 in 2022)”;

- a shift to virtual proceedings;

- expansion of GPS (note: we previously wrote about a shortage of electronic monitoring bracelets in Milwaukee County. The report did not discuss this shortage);

- a hold on admissions to prisons and juvenile facilities (our note: the state prison system is run by Gov. Tony Evers’ Department of Corrections, a state agency. We would also note that probation and parole virtual supervision, lack of revocation for new crimes and drug offenses, prison staffing shortages, and the state’s early release program are additional factors to consider);

- suspension of jury trials, consolidating 14 felony and seven misdemeanor courts into three courts;

- the Supreme Court’s suspension of statutory deadlines for non-criminal jury trials. The latter helped “pave the way for a vast expansion of backlogs of pending cases,” the report says.

- Other changes to the pretrial system were made in 2020 and again in March 2020 “to reduce pretrial supervision caseloads by bringing individuals who met certain criteria down to a reduced level of attention instead of requiring formal supervision,” according to the report.

- We would also note the DA’s new practice of giving more people summonses (pieces of paper) ordering them to appear in court rather than booking them into the jail. Back in 2021, we interviewed DA John Chisholm in a courthouse hallway. Chisholm revealed in that interview that officials were using a previously unreported process – which he blamed on COVID – to hand many arrested suspects “summons” (a notice) to come to court for their first appearance, rather than book them into the jail and requiring them to bail them out at all. That means that many offenders were left on the streets after their arrests, and it was left to them to do the right thing and show up for their first court appearance.

There was also a significant procedural change to “restrict bookings” into the jail for misdemeanor and nonviolent offenses, with some exceptions for incidents like domestic violence. [We previously wrote about that issue here. We also wrote about a new MPD practice not allowing arrest for municipal and misdemeanor warrants.]

In January 2022, more changes were made as the Omicron variant hit the news. Universal screening interviews (which had resumed in September 2021) were “temporarily halted for a month before gradually phased in again in March 2022,” the report says.

Jury trials were phased in again in July 2020 and the number of courts in operation expanded from three to seven, it says.

“Additional phases of in-person resumption for hearings and jury trials began in September 2020, May 2021, and September 2021,” the report says.

Between April and September 2021, the county’s Out of Custody Court – which handles initial appearances for people not in law enforcement custody – conducted 700 additional initial appearances that had been delayed to help the backlog, it adds. However, as we will discuss in detail in a future story, the felony backlog remained severe as late as December 2022.

By mid-December 2022, intake court for defendants in custody had returned to in-person operations.

“In addition to the use of county-appropriated ARPA dollars mentioned above, justice system leaders received notice in March 2022 that they would receive $14.6 million in ARPA funding from the state’s allocation to address the courts backlog,” the report says.

“The funds were intended, among other things, to allow the courts – as well as the District Attorney and State Public Defender – to hire additional staff and open additional courts. Ultimately, state ARPA funds also were used to hire a Mental Health Treatment Court coordinator and to help provide for 24/7 GPS monitoring of pretrial individuals.”

Coming tomorrow in part 2: How the ACLU’s Collins Agreement affected proactive policing in Milwaukee, starting in 2018, well before the pandemic. This story can be read here.

Table of Contents

![WATCH: Elon Musk Town Hall Rally in Green Bay [FULL Video]](https://www.wisconsinrightnow.com/wp-content/uploads/2022/04/Elon_Musk_3018710552-356x220.jpg)

![The Wisconsin DOJ’s ‘Unlawful’ Lawman [WRN Voices] josh kaul](https://www.wisconsinrightnow.com/wp-content/uploads/2025/03/MixCollage-29-Mar-2025-08-48-PM-2468-356x220.jpg)