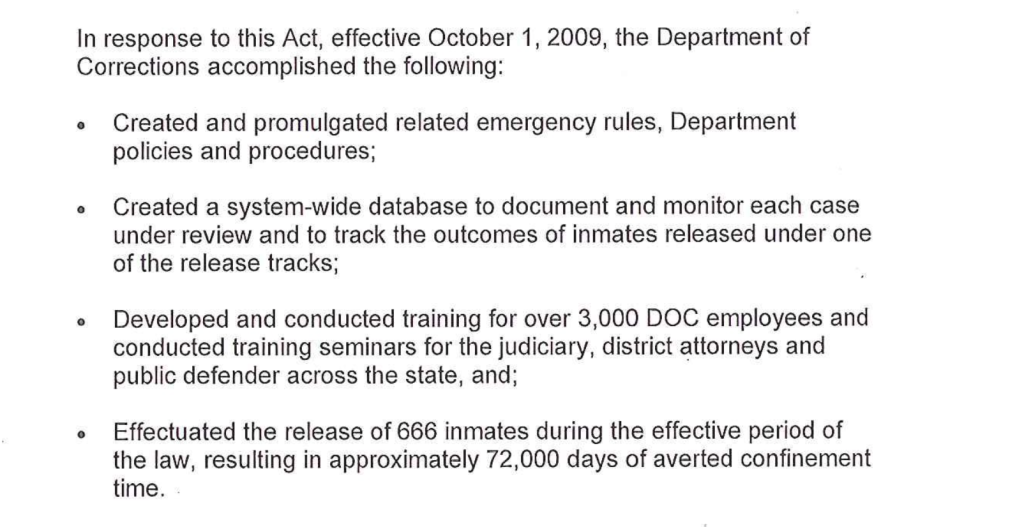

Liberal Judge Susan Crawford was Democrat Gov. Jim Doyle’s top lawyer when Doyle implemented the mass release of criminals from state prisons.

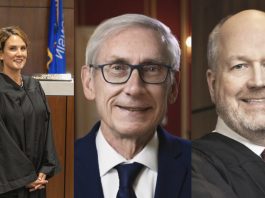

In response to this Act, effective October 1, 2009, the Department of Corrections created emergency rules and “effectuated the release of 666 inmates during the effective period of the law resulting in approximately 72,000 days of averted confinement time,” a 2011 letter from the Corrections Secretary says.

In 2011, then corrections secretary Gary Hamblin sent the letter explaining that 2009 Wisconsin Act 28 “created seven new early release tracks for non-violent inmates incarcerated in the adult prison system. The intent of this legislation was to create an array of release mechanisms….” However, far from being non-violent, the release provisions even applied to some homicide offenses.

The letter covers the 2009-2011 budget. Crawford was Doyle’s Chief Legal Counsel from August 2009 through January 2011. She also worked as Chief of Staff to his Secretary of Corrections from 2006-2007.

Crawford, a liberal, is on the ballot today in the state Supreme Court race, facing former Republican Attorney General Brad Schimel, who has earned the endorsement of most of the state’s sheriffs. More recently she has been a Dane County judge where she frequently has gone under prosecutors’ recommendations, even for child rapists and molesters. She has given a series of violent offenders light sentences. In between being a judge and working for Doyle, she served as a private lawyer, representing a foreign opioid manufacturer against the interests of Wisconsinites, and filing lawsuits to overturn Act 10 and Voter ID. See her record here.

How bad was Doyle’s early release program? In January 2011, this author wrote a sweeping investigative piece for the then-Wisconsin Policy Research Institute. The article analyzed 22 of the inmates who received early release in this time frame to see who they were:

- In nearly 70% of those releases, elected judges had previously denied the criminals’ release from state prison, saying it was not in the public’s interest. Prosecutors had objected in some cases.

- In one case, a felon’s early release had previously been denied three times by a judge.

- The inmates had serious felony records. One was a 12-time convicted felon. One was a fifth-offense drunk driver who had already been revoked and who previously caused injury while driving drunk.

- In more than half of the cases, the freed inmates were in prison because they had already been revoked.

- One inmate was being held on a detainer and was in the country illegally before being caught in a cocaine ring.

- One woman with health issues was serving a homicide sentence when released.

- Some of the released inmates were habitual criminals.

- Some of the inmates had violent and weapons criminal histories.

- Far from affecting only non-violent inmates, nine homicide offenses fell under the new sentence modification provisions.

Doyle’s early release program allowed inmates a number of new ways to get free, among them expanded provisions for age and health.

The new provisions on age were so sweeping that they theoretically allowed some of the state’s worst inmates a chance for release at age 60. The change meant inmates serving life sentences could seek release at age 60 even without terminal illness. Now they just had to show “extraordinary health circumstances,” which could be defined as age. The change came in 2009.

The article says inmates ranging from notorious murderers to convicted cop killers theoretically qualified.

Doyle’s changes yanked release authority from elected judges and gave it to bureaucrats.

![WATCH: Elon Musk Town Hall Rally in Green Bay [FULL Video]](https://www.wisconsinrightnow.com/wp-content/uploads/2022/04/Elon_Musk_3018710552-265x198.jpg)

![The Great American Company [Up Against the Wall]](https://www.wisconsinrightnow.com/wp-content/uploads/2025/03/MixCollage-29-Mar-2025-09-08-PM-4504-265x198.jpg)

![The Wisconsin DOJ’s ‘Unlawful’ Lawman [WRN Voices] josh kaul](https://www.wisconsinrightnow.com/wp-content/uploads/2025/03/MixCollage-29-Mar-2025-08-48-PM-2468-265x198.jpg)